““For us, there is only the trying, the rest is none of our business.” -T.S. Eliot”

There’s a golfer that every other golfer dreads. This troubled soul has an insurmountable chasm between how good they think they should be and how good they actually are. That chasm is expressed with pouting, tantrums, cursing, and generally inexcusable behavior.

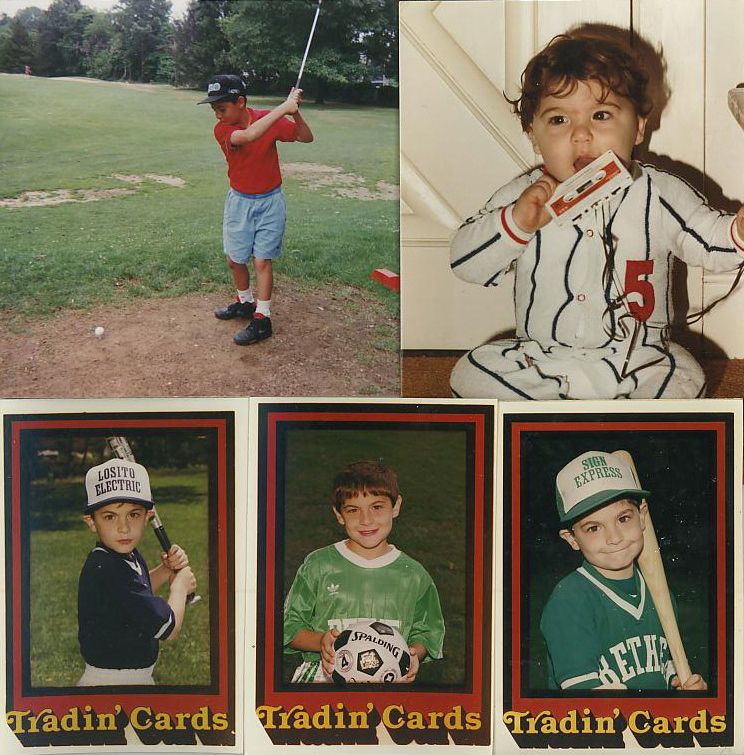

Until the age of sixteen, I was that golfer.

I threw clubs around the course when I wasn’t breaking them over my knee. I was vicious to everyone around me. A round of golf lasts for hours. Some of my dad’s finest moments were his patience with me during these rounds.

My high school English teacher, Tom Hackett, had the bad luck of playing a round of golf with me in the summer before my Junior year. Yet his misfortune in being around my golf-related awfulness later became my great fortune. The following year he gave me the school’s writing award, and my prize was the book Golf in the Kingdom. It was written by Michael Murphy, founder of Esalon, the famed West Coast retreat center. In the book, a fictional version of Murphy plays one round at a legendary Scottish course with a mystic golfer named Shiva Irons, and it forever changed his game, as well as revealed a way of being present for this life that stayed with him for decades.

Much like the fictional Murphy, I was quick to fudge the score and drop the ball to a place where it was easier to hit. I took to heart the lessons of Shiva Irons that it’s better to learn to play the ball from the difficult places than to immediately achieve the score I desire. Reading the book transformed my golf game, and marked a potent shift in how I related to competition.

The book initiated me into what I’m sure will be a lifelong investigation of what is the most skillful relationship to winning and losing.

My childhood was not very happy, but upon reflection about the joys of growing up, winning was a consistent source of joy. Kind of. My fondest memory from my years of playing goalie in soccer was a coach giving a speech after a game about how great I played during our team’s 5-0 loss. I also remember pouting an entire evening after a little league baseball playoff win, because I didn’t get a hit. It wasn’t really about winning—it was about me.

There might be a rush from the praise of such successes: saving the goal, beautifully delivering a line in a play, Yahtzee. Yet winning in this regard is not a stable refuge for happiness. Losing happens, too. Losing happens often if you hazard trying things you’re not already good at.

My identity as a sore loser was not confined to the golf course. I remember young me throwing the Nintendo console across the room when I was about to lose a game to my brother Andrew. This was standard practice in our house.

Those who only know me as an adult are probably surprised to discover what a brat I used to be. I credit my meditation practice with the transformation in my capacity for winning and losing with more grace. Yet I’m still far from indifferent about outcomes.

James Baraz, a wonderful meditation teacher, tells a great story about how meditation trains the mind to deal with victory and defeat in his book Awakening Joy. James was an avid New York Knicks fan when he first started meditating in the 70s (things change--he's now a Golden State Warriors fanatic). Back in the 70s, he was first experiencing the calm that’s possible with a meditation practice, he had a frightening thought: “What effect would a full-on commitment to meditation have upon my enthusiasm [for the Knicks]?” The question was important enough to become the first thing he asked his teacher Joseph Goldstein.

Joseph responded, “Don’t worry. I think you’ll still be able to enjoy the games just as much. If anything changes, it will probably be that you’ll be able to get over a loss sooner and with less devastation.”

In part two of this post, I’ll share how meditation not only takes some of the sting out of losing, it also teaches us to salvage wisdom from our losses.